Training this new old body

What works and how it feels to return to lifting after COVID, long COVID-ME/CFS, and one year of sickness inactivity

I trained yesterday. It was a simple routine made of squat, bench press, and deadlift. There is a story about why I chose a full body, full lifting repertoire, one that will be easier for the folks following this page to understand than my other readers.

Like everyone, I am not the lifter I used to be. But I am not the lifter I was in 2017 (my last meet, when I still set a national record), or 2019 (the year before I got COVID-19), or 2022, when long COVID’s chronic pain made my training sessions frequently very painful and when, one day, the pain was so severe that I stopped lifting. I am not that lifter in terms of my sheer physical strength, in terms of my ability to train, and I am not that lifter in terms of belonging to a community of lifters. Disease took away all of that, and when it also took away my ability to lift, I lost touch with everyone and all the news about the strength sports.

I became extremely weak and ill.

If you had to guess, where would you say the greatest impact on my lifting, measured in lifted lbs/kg, happened? Between 2017, the last competition, and 2019, a complicated period with several health issues, where I still trained but not competitively? Between 2019 and 2022, when I had COVID, stopped training for months, struggled and clawed my way back to training, in full blown long COVID? Or between 2022 and now? It was the last one.

Until 2022, I was definitely still a lifter. I was a lifter in my training habits, in my anthropometric measures, in my food habits. For a couple of months after that afternoon, in early August, when I lifted for the last time, I didn’t feel much change in my body, in shape and basic abilities. But instead of experiencing an improvement in my chronic back pain, I quickly started getting worse and worse, until I became pretty inactive in 2023. I don’t know exactly for how long I was almost completely inactive. I’d say almost a year.

By Fall and Winter, I started moving again. Longer and longer walks in my neighborhood. I even got a vest, where I took my pepper spray and noise deterrent, after I got seriously bit by a dog. No, the dog danger, very real in my neighborhood, didn’t stop me. The heat did, so I bought an “under the desk” treadmill. I was active again.

I only started lifting again in May.

I guess many of you reading this wonder why I stopped lifting that afternoon in 2022, and didn’t go back to it when the pain got better. One reason is that the pain didn’t get better for a while. The main reason, though, is that the day the pain on the deadlift made it impossible to lift again, I got scared, and did what I do when I’m scared: I dig into the medical literature until I know what I’m looking at, what are the explanatory models for it, and more or less, what to expect. My reaction to fear is literature review (“research”). And there it was: things that look like ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome), as long COVID does, are not only characterized by “post exertional malaise”, but there is evidence that exercise may possibly make the chronic pain worse. What kind of exercising approach helps and which ones can harm the person, I couldn’t infer from my literature review. The pain I was in, the fear, and the depression/apathy that engulfed me made me actually decide to stop lifting. But there was an “until”. “Until I figured out which exercises were safe”, “until I felt safe lifting again”, but most of all, “until the pain got better”.

The “until” never came, and I stopped reading news on powerlifting, weightlifting or strongman. I stopped coaching before that. I disappeared.

In May, this year, I decided that I was tired of waiting for that “until” and started lifting again, no matter what.

The return is surreal, to say the least. The moment I touched Sophia, the Texas Powerbar, again, in my gym, was almost as magical as the day I first touched an Olympic bar. We danced (squatted), and I was clumsy, but - wow - alive. Who’d have thought. And when I held Rhea, the Texas deadlift bar, I felt funny, but comfortable. Comfortable in my body. Kind of like coming home.

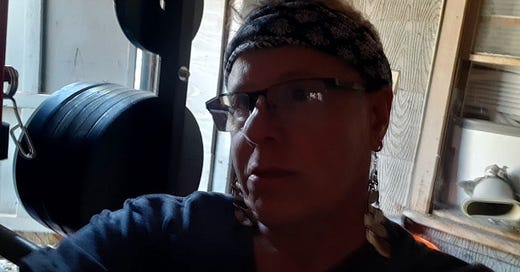

I think it was more or less then that I bought a mirror. A simple door mirror. My cats liked the mirror and I got another one for the bathroom. I looked at my body for the first time in more than a year. It was shocking. I remember feeling my legs becoming thinner and thinner a couple of months after I stopped lifting, but I think I didn’t expect… “this”. I can barely recognize myself, but “it” lifts. The mirror is highly depressing and liberating, at the same time. That’s it, that’s my body, there is no changing mental representations of it. There is a lot of wasted energy in these states of uncertainty.

In May, I first tried using Planet Fitness, to adjust back. My reasoning was that I was so weak, that maybe guided machines would be better at this stage. It didn’t work.

My home gym is a mess, not even finished yet, but the rack and the bench are available, as well as a very small platform. That was it, no more waiting. The first lifting regimen I adopted was not productive. The volume was too high for my condition:

Squat: 5 sets of 10 repetitions (starting with the empty bar); Bench press: 5 sets of 10 repetitions (empty bar); Deadlift: 5 sets of 6 repetitions (starting with the bar and two 10lb bumper plates).

In the first attempt, it was hard to do all three lifts, even with no weight on the bar. For a while, I did just the bench press and the deadlift. I was too tired, and too sick, and the squat was the hardest for me. Then the heat came, the AC was not installed yet, and training became difficult, with many skipped sessions.

There was no improvement. I was always tired, I didn’t add weight to the bar, and, sometimes, pushing through the session was hard. Back to the medical research literature I went, and found out that, in more recent years, some studies discriminated between types of exercise on ME/CFS patients. The most impacted function for us is cardiovascular endurance, and high volume anything is the hardest. So I changed my training protocol and reduced the volume to 5 or 3 repetitions per set.

The increase in lifted weight, up to now, has been almost linear.

Squat - 20kg/45lbs for 10 repetions to 54.5kg/120lbs for 3 repetitions

Bench press - 20kg/45lbs for 10 repetitions 54.5kg/120lbs for 3 repetitions

Deadlift - 30kg/65lbs for 6 repetitions to 76.5kg/168lbs for 4 repetitions

As I write this, I smile, because “linear improvement” is not what I feel at the gym. I feel weak as hell. I get under the bar with less than 60kg on it, and recognize the sensation. It’s what I used to feel under 140kg(308lbs)+, which I did for reps. On the bench press, I am lifting almost as much as in my first ever competition, where I lifted 60kg. Not really: 54.5kg is not my 1RM today, it’s more likely 60-65kg, but it’s incredibly weak compared to my “any day” strength of the recent past. As for the deadlift, I remember this weight, too: it’s the heaviest weight I lifted in a commercial gym when I felt, as sure as I ever was, that I absolutely loved this thing. That was almost 20 years ago.

As weak as this is, it is still a dramatic improvement in a short time: the actual improvement started a couple of sessions ago, when I reduced the volume. This is just a pretty fast neural adaptation to the stimulus, expected in athletes.

I’ve always been a very good bencher, but benching as much as squatting wasn’t expected. My difficulties with squatting are important to observe, and plan accordingly.

Since 2011, my home gym has always been my refuge. It’s where I always felt most at home. I guess one of the first lessons I learned here is that I should never have stopped lifting for more than a week, and that I should have kept my training routine, at my home gym, even with a dramatic reduction of volume, intensity and variety of exercises. From a reduced capacity under routine training back to a fully trained capacity takes a certain effort. From a state of severe strength and muscle loss and inactivity into a fully trained capacity, it is going to be an order of magnitude harder.

Another lesson is to trust “old learning”. The lifts are movements with which I am familiar at a very deep level. They have been repeated, automated, taken to their maximum output, and redefined the body doing them. As soon as I touched the bar, the setup was instinctive, and I recognized actions in my body that hadn’t happened for an eternity. An year, actually. The feeling is that I don’t only know them, but the lifts are “what my body does”, something intrinsic to it.

And that is why I chose to start training with the lifts. One could say that at the level of damage, injury, chronic inflammation and pain this body is, it was not the smartest choice. Guided machines allow us much more precision in adjusting variables, and are considered safer. A damaged body needs safety. I considered all that, but the day I couldn’t go to the commercial gym and, instead, went to my garage gym to lift weights, I realized I was wrong. That I could still work with safety, with empty bars or minimal weight, and that I had good command of my body in the lifts.

I decided to start there, with the three familiar lifts, gaining strength back. Progress seems to work differently for folks with these strange inflammatory disorders, so I believe the best approach is to be minimalist, and secure the progress lines.

I dislike the word “humbling”, but this experience is humbling. I am a coach, I design complex training programs, with non-linear progressions in each lift and in combination, I play with variables and segmentation, and here I am, hours of reading in primary sources to manage a program made of one routine, the routine being made of the three lifts at minimal intensity and minimal volume. That’s all.

That leads me to the last lesson. That navigating aging successfully is requiring of me the commitment and attitude of the two things I am good at. The first is being a scientist: studying the literature (what folks call “do your own research”, but I’m a researcher, and I swear it isn’t), science-based planning, and collecting and processing data about my performance (now that is research, but folks don’t see it as such). The second is being a high performance athlete, where routine and discipline are crucial, where focus is essential, where nutrition is the difference between success and failure. In high performance athletics, it is between winning and losing. In aging, it is between illness and health.